Extracts from this article are printed in the Guardian today (18 July).

This is the second article from my series of interviews with people around the country who are affected by this appalling government’s welfare changes, NHS reform and cuts. This report is from the southwest.

The interviews from Weymouth are with a group of older men who were in and out of homelessness and battling to keep their jobseekers’ and employment and support allowances.

The names of people on jobseekers’ allowance or ESA have been changed and marked *. Most of these people were going through Atos work capability assessments and were concerned that the mere act of giving interviews would be construed as fitness for work. There are accompanying audio recordings.

There is also a list of policy changes and cuts which affect each person at the end of each section.

———————–

Weymouth, May 2012

Olympics 2012 costs-in-austerity controversies:

Stone mushrooms cost more than £330,000.

Local hoteliers fear thousands in losses during the games

Sandcastle costing £5000 demolished

Image: Pier at Weymouth, May 2012.

Of all the cowflop that David Cameron speaks, there is no bigger pile than his deceitful and misleading “culture of entitlement” line on people on benefits.

Lives on benefits are not, as Cameron would have us believe, simple and sorry stories of unreal “expectations” from people who believe “the state will support you whatever decisions you make… you can have a home of your own… you will always be able to take out, no matter what you put in.”

It’s one of modern politics’ most loathsome sells: this notion that people who need state support hold any cards, let alone all of them. The idea of a culture of entitlement is entirely romantic. There’s nothing left for anyone to feel entitled to. No aspect of taking state money in this day and age is painless, or liberating – except, perhaps, if you’re a bailed-out banker.

For the rest, a life on benefits is an appalling tale of financial and personal reduction, particularly when you’ve no hope of buying yourself back by finding a job. You must have the state in that case. You can’t do without it. Your desperation, though, means that the state also has you.

I’ll give you an example of this reduction from Weymouth. It will sound tiny, but it wasn’t. It’s probably common, but it wasn’t insignificant. At the time, I was worried – I thought there was a chance that I may have put someone’s benefits in jeopardy. It was probably a small chance, but the thought did occur to me.

It all started merrily enough. I was horsing around in a carpark with Sean Needham* (in his 50s and made redundant from a Woolworth’s warehouse when Woolies went bust), Pete Gyte* (ex-armed forces), Mike Gale* (also ex-services) and H*, Mike’s cheerful, turbo-charged, Alsatian when Needham made a sudden decision.

He invited me to the next meeting of the job club that the men said they had to regularly attend as a condition of collecting their jobseekers’ and employment and support allowances. All three men were in their late 40s, or early 50s. All were unemployed and all had been homeless from time to time over the years.

Nobody seemed entirely sure what the job club was for (“we’re supposed talk about getting work and CVs,” Needham said, vaguely), but they could see two clear advantages to it for me.

The first was that they thought it would give me some insight into the hoops they had to jump through to keep their benefits and/or find employment in their challenging patch. Employment rates in the southwest are among the country’s best, but unemployment has been on the rise. If you’re a drug addict, or an alcoholic, or have serious mental health problems, or a history of homelessness – well, the guys said that it might happen, but it might not.

“I mean – come on,” Gyte said when we touched on the topic. “They reckon everybody’s fit for work, but if I had a company, most of the people I know – I wouldn’t let them in the door! Operating expensive machinery…?”

The second was that there was a sex shop somewhere along the way. There was no real advantage to that news, I suppose, except that it made us all incredibly funny for the rest of the night.

“You can get a pair of knickers first!” Gyte giggled.

“No crotch for me,” I said, which was, obviously, hilarious. The entire conversation seemed hilarious – a whole lot of giggling and snorting about David Cameron, Tories, government, CVs and dildos.

It was only when I turned up to the job club a few days later that I realised I’d made a very bad mistake. There was nothing amusing, or trifling, going on here.

The people who ran the job club were horrified to find that a journalist had arrived for it. They oozed concern – and fair enough, in many ways. Most of us are terrified for our jobs, or funding, or reputations, or everything, and rightly so. Last year, just as an example, Hammersmith and Fulham council tried to sack careworkers who supposedly leaked details of a mental health supported living hostel closure to me for this Guardian article. People are right to worry. Fear, concern and tension shut doors (although to be fair, the staff at the job club did say that I could probably come back if I made an appointment).

Sean Needham, though – the guy who invited me to the job club in the first place – had no power at all. That’s the point. You don’t if you must rely on benefits for food and housing at a time when work and sympathy are almost impossible to come by. I caught his face as I left. He was obviously worried about having invited me. He was sitting very quietly in a chair against a wall – an older man, dependent on other stressed people for income and possibly, I thought at the time, with that income flashing before his eyes.

I met him by Weymouth Pavilion a few days later. “Did you get into trouble for inviting me?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “Not really,” he said, shaking his head. “No.” I thought about fear and forced passivity for many days after that. Welfare’s enemies yabber endlessly about unemployed scroungers lying around in the sun on disability living allowance and ESA, but, you know – in Cameron’s dreams. I see little evidence of enjoyment, or a sense of entitlement, here.

Policy affecting, or likely to affect, these people:

– New limits (from 30 April 2012) of eligibility for contributions-based employment and support allowance to a year. Being found fit for work and placed on jobseekers’ allowance.

– Government proposals to cut benefits to people with drug and alcohol problems

————

It rains and rains when I’m in Weymouth: thunderstorms, storm alerts and gummy, warmish downpours that turn cold the instant you leave cover. I wouldn’t want to live outside in this weather. Nobody does.

“I actually went round to the council one morning,” Pete Gyte tells me, “because I was so done in from sleeping on the pier. It was chucking it down with rain – gale-force wind – and I only had 30 minutes’ sleep, because of the fucking generators going on the bastard ferry. I walked into the council and I said “why don’t you just take me to the hospital and give me a lethal injection?””

Gyte sometimes talks Death when discussing routes out of long-term unemployment and homelessness. He’s amusing with it, but he does throw it in.

“You can’t imagine it, can you?” he asks one morning when we’re having breakfast at Soul Food, a charity which serves meals and offers accommodation advice and support from a centre up from Weymouth Way, not far from a monolithic Asda (Soul Food is managed by Wendy Selway).

“Like – everything you’ve got now is gone. [You’ve got] no money. As soon as you change anything, your housing benefit is gone. They put me off ESA and put me back on jobseekers’ (he was recently found fit for work after an Atos assessment. That means his income is about £65 a week). I went five weeks without any money and I went to the council and three bloody forms I had to fill in. I said – “excuse me. How many trees [are you using for these forms]? I can’t wait for you to wipe out the rainforest, because I won’t have to worry about paperwork any more.”

It’s not the world’s greatest mindset, says Soul Food outreach worker Angela Barnes, but it’s one plenty end up with as doors to jobs and housing shut. She’s expecting more of it. It doesn’t matter how bitterly the likes of the Telegraph’s Brendan O’Neill complain about references to suicidal claimants entering debate about welfare. The fact is that sometimes, people talk about suicide. I thought of Gyte when I read O’Neill’s “article.” Gyte laughed a lot about life on the streets, but he did say that there were times when dying seemed the clearest route out of it.

Barnes, who is in her 50s, and likeable and passionate, has about 40 people on her caseload – people with mental health problems, drug and alcohol problems, people who often have nowhere to live. The need is there and growing, she says, whether the government thinks it should be or not. Depriving people of benefits and housing doesn’t cure mental health problems. When people lose jobs, benefits and housing, they don’t all suddenly race off to start a new business, or get into sales, or whatever. They go looking for help and if they don’t find it, they fall.

For some, the harder finding a job and a home becomes, the harder they find it to rise to landing either.

“[Sometimes], the guys [men on her caseload] come to me and say – “Oh Ange – we’re not getting our benefit. We need to phone the council to see if we can get on their list.”

“I say – “Okay, phone them up then. It’s very simple. You just pick the phone up and make a phone call” [They say] – “Oh, can you do it for me?” That’s when I found out that it’s not just a case of picking up the phone and making a phone call.” The problem might be alcoholism. It might be drug addiction. It might be mental health. There’s often shame in there, too, Barnes says – “the guys have a lot of pride.”

In the video below, Barnes talks about alcoholism, homelessness and work capability assessments. She also talks about the speed with which problems like alcoholism, homelessness and unemployment can catch up with anybody. They caught up with her several years ago. She had a home, a fiance and a business, but then her business began to fail and her housing benefit was suddenly stopped. “I found myself out on the street. I’m like – hang on. I don’t quite understand where this has gone.”

Her landlord decided he wanted her out. She says that her housing benefit problem would have been sorted out and he would have been backpaid, but that he didn’t care. “This is what social landlords are frightened of. So, I spent [that year] until December as a homeless person. It’s not good.”

As Barnes says – you don’t need great foresight to understand that housing benefit cuts, tightened benefit criteria and unemployment will put more people on the streets. Shelter figures show that the number of households accepted as homeless in Weymouth and Portland rose sharply in the first quarter this year. The number of households on council housing waiting lists increased from 3874 in 2010 to 4206 in 2011. In September last year, Shelter reported that the number of people living in temporary accommodation in Dorset was up by ten percent.

God knows how things will look in a few years’ time. It is extraordinary to think that only ten or 12% of cuts have been implemented. Greek levels of homelessness and hardship seem inevitable.

Four years, John Krinsky said when I interviewed him earlier this year about US welfare reform. Give it four years and then you’ll really see something. Krinsky, a City College of New York City political science department chair and author of “Free Labor: Workfare and the Contested Language of Neoliberalism,” said that New York had seen a similar phenomenon – “about four years after New York City started reforming welfare [in the late 1990s], we started to see a spike in the number of homeless people. That has continued unabated.” There’s nothing to say that won’t happen here.

Certainly, the guys in Weymouth see a relationship between their own losses of employment and slide into homelessness.

“I lost my job and I couldn’t afford to pay my rent,” Gyte says as we sit at our tables, trying to eat the toast that an amusing, if slightly distracted, Scots guy called Paul Taylor* is burning for us on a bench at the front of the room. “As that Norman Tebbit said, I got on my bike and went looking for work, but well – yeah. There ain’t no jobs out there.”

“His bike lasted longer than we hoped!” Taylor yells across the room at us as he fans toast-smoke away from his face with his knife.

Gyte ignores him. “This,” Gyte says, proudly, “is my background,” He hands me a typed and beautifully formatted CV carefully (Cameron would surely be pleased to see it). The CV is printed on a thick, chic, patterned paper which has been styled to look like parchment.

“There’s military experience in that background,” Gyte says, pointing at the paper. The CV also lists Gyte’s IT skills. He says that he applied for an IT job earlier this week. He doesn’t hold out much hope for it, but he has to apply and attend jobs clubs and training to keep his JSA.

Mostly, Gyte talks about good times lost – his and the country’s. “In my lifetime, I’ve seen all the different technology and that… I’ve had the bikes, I’ve had the cars, I’ve had the women and the wine.” On Britain: “they let people buy [council] houses and then they sold them off without replacing them…you can’t base an economy on just a few houses and shops. We used to build ships and things.”

He talks a lot about the economic crisis in Europe and is concerned about high unemployment. “Spain is at a 22% unemployment rate and we’re going to hit 11% in the next ten years.” The problem, he says, is that “there are too many people here.” That’s a line I hear again and again as I travel – that there are too many people in the UK, that the place is too crowded and too competitive and that there isn’t enough to go around.

“[You can see what is happening],” Taylor says. “The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.” Taylor says he also used to have it all – a job, money and women – “but I was trying to fill myself up with as many fucking drugs as I could get my hands on. As much money as I could steal, or make… but it was drugs for me… not any more though. I’m in AA. I’ve had seven years sober.”

Right now, he wants to “get them [the Tories] into Parliament Square, make them swear allegiance to the people, hire a couple of top military commanders, march them into parliament, round the lot of the toffs up and get the lot of them round the dock, so we can see what they’ve been up to.”

“You realise that she’s recorded that!” Gyte laughs. “[They’ll come here, because they’ll be thinking] “look at what the poor are going to do to us.”

“What is happening now is that you’re getting the rise of fascism,” Taylor says more seriously. “Racist groups. It’s happening in Greece and it’s happening in France…[politicians] feeding on racism.”

Here, Gyte says, the problem is that “the government don’t give a shit about the people. Just their friends. They’re given massive tax breaks and they’ll never spend it if they live for another 100 lifetimes. You got people at the other end who can’t even afford to put their heating on and buy some food. They’ve got to be the biggest bastards ever on the planet. They’re not kings. They don’t look after their people.”

There’s one rule for them, says Taylor, and one rule for the rest of us. “What about that scandal? The expenses, you know, that some people are claiming for pornographic DVDs!”

“And a moat…” a third man says.

“They’ve got no hope,” Taylor says. “Just got no respect. The kids have got no respect now. [Leaders need to] lead by example. Right now, they’re making it up.”

Anyone who thinks living outside is a laugh should try it, Gyte says. “It was out in the streets [for me] wherever I could put me head down – and then you have the police coming along saying “you can’t sleep there.” In the end, “I was helped out by a few guys who put me in a tent for a few months…[Ultimately], the British Legion got me in a room in a house.”

Finding landlords for housing benefit tenants is, Barnes says, “impossible.”

“I know the issues that they (landlords) have – [they worry] that [because] the guys aren’t paying out of their own pockets, there is a danger that they won’t look after the place properly. If they’ve got addictions, or mental health problems, that just increases the burden.”

Policy changes affecting, or likely to affect, these people:

– New limits (from 30 April 2012) of eligibility for contributions-based employment and support allowance to a year. Being found fit for work and placed on jobseekers’ allowance.

– Government proposals to cut benefits to people with drug and alcohol problems

First audio recording from this interview:

Transcript from this interview (PDF 42KB).

Second audio recording from this interview

Transcript from this interview (PDF 50KB).

————-

Totnes

Polls point to a country united by Cameron’s divisive welfare cuts, but I find a nation linked by fallout from government policy – welfare changes, NHS “reform”, cuts to social care. I find agitation, tetchiness and uneasiness, even in places which look, if you base these things on looks, beyond those things.

I think about this when I arrive in Totnes, in Devon.

Totnes is a beautiful market town which is balanced on top of a long, lung-busting hill rising up from the river Dart. You’re prepared to part with a lot of money for a coffee and a seat when you get to the summit and sometimes, you have to. Totnes is a place of startling charm and Londonish prices.

It doesn’t immediately speak of uncertainty, but it does soon after. Battles for services and cherished institutions like the NHS rage here as they rage everywhere. Nowhere is untouched.

The speaker in this video is Trina Furre, a print and web designer who works out of a bright, open-plan office in the middle of Totnes. She is also a volunteer support worker for people with arthritis.

Furre relies on the NHS and has for many years. She developed rheumatoid arthritis when she was just 19 – “so, all the way through I’ve been under the care of rheumatology departments wherever I’ve been living.”

When we meet, Furre, along with other arthritis sufferers, is concerned about the future of a hydrotherapy pool at Torbay hospital.

The pool, Furre says, “is fantastic” for people with arthritis. “It gives you the freedom to move. [With] arthritis, if you’re having a flareup, moving is painful, so to get in a warm, supported environment where you can relax and move around pain relief in itself.”

Rumours about the pool’s future began to swirl several months ago, raising hackles and antennae. Furre and fellow campaigner Clare Spooner says pool users got wind of a questionnaire which asked people how far they’d be prepared to travel for hydrotherapy.

Then they heard that a fracture clinic wanted to expand and had an eye hydrotherapy’s space. Nobody knew exactly what was being said – were pool users looking at a cut, a move, or a closure? Torbay and Southern Devon Health and Care NHS Trust was at considerable pains to explain to me that this was not a cut: “This is something we have looked at as part of standard operational effectiveness – NOT in terms of potential efficiencies….there are no plans to make changes to the hydrotherapy service at Torbay Hospital at the current time.”

“On the noticeboard at hydrotherapy, they pinned up a list of various [public] pools that you could go to instead,” Furre says. Campaigner Clare Spooner tells me that she visited each pool and wrote a report which showed why people with disabilities could never make use of public pools.

Says Furre: “There were steps going down into these pools, there were no handrails, there were no hoists to get people into the pools, the water was too cold, the changing rooms were totally unsuitable – it was just absolute nonsense to say that people with disabilities could use these public pools.”

As she says in the video, Furre also worries about a future where accessing healthcare isn’t as straightforward as it has been (that is, if it is no longer free at the point of use).

Right now, she is taking “a very expensive new drug… It costs about £10k a year per patient, these injections – and it’s been pretty life-changing for me.”

In the UK, she says, “if you qualify medically, you [pretty much] get it,” but that isn’t the case in other parts of the world.

She can see this from posts on an arthritis support forum which she follows.

“Because it’s [the forum] worldwide, [I can see people talking about the] new biological drugs. A lot of them are going – “Will your insurance company cover the cost of this? Which ones will they pay for? Which ones won’t they pay for?” It is just so different than living in fear that [your] insurance company is going to stop the funding.”

“The thing that really worries a lot of people with chronic illnesses is that if this thing with [needing to buy private health] insurance comes in, there would be no insurance that I could get. Nobody [no insurance company] would touch me with a barge pole.”

Doesn’t matter where you go. People all over feel threatened and are waiting.

Policy changes affecting, or likely to affect, these people:

– Concerns that NHS reforms will ultimately lead to charging for services

—————

Poole

Even in well-off, conservative (small c) places like Poole, foundations are rattling.

I spend a morning on Longfleet at Poole foodbank with manager Lorraine Russell, who notes two significant recent trends at the foodbank.

The first is that demand for food parcels has doubled (and almost trebled), in two years. The second is that the foodbank’s biggest client group is now people on low incomes – so, people who are working, but can’t feed themselves properly because of rising rent, mortgage and living costs, and low wages.

“Before, the primary reason (for needing food parcels) was benefit cuts or delays, but now that’s been overtaken by people on low incomes. We used to get very few low-income people, but that has taken over.”

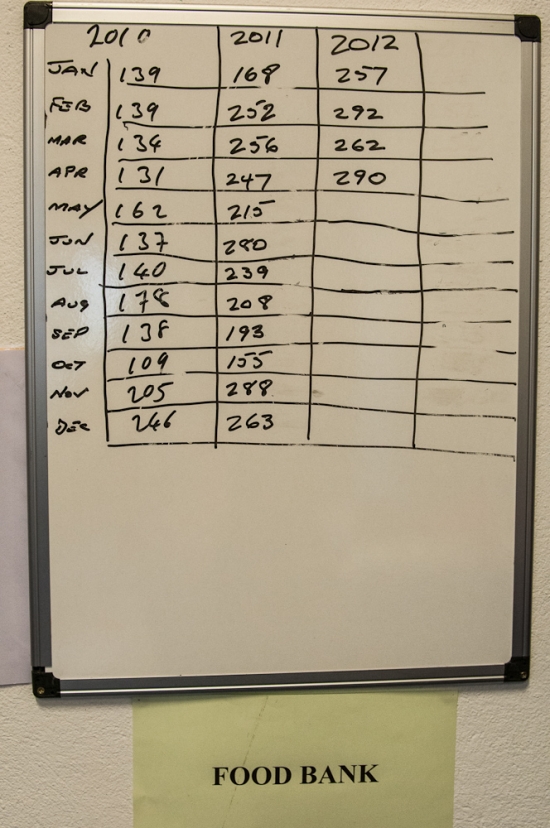

The picture on the right shows a noticeboard on the foodstore wall at Poole foodbank. The noticeboard displays the year- on-year and month-on-month increases in the number of foodparcels the foodbank is distributing.

on-year and month-on-month increases in the number of foodparcels the foodbank is distributing.

Russell says that about 2763 people were fed through the foodbank last year. Returning customers are also a new trend: the foodbank is meant to operate as a short-term, emergency stop-gap for people who can’t afford food, but “numbers are growing and we are seeing a lot of people on a fairly regular basis… the idea is that people come three or four times, over which period their presenting problem – whether it is benefit cuts, or [benefit payment] delays, or debt, or whatever it is – can be sorted out, but it’s not happened like that.” In other words, people’s financial problems are not being solved.

Russell believes that people want to work – the problem is that paid work doesn’t necessarily cover the bills.

“I had a guy come in last week. He was working in Southampton, but living on the streets – so he’s living off the streets and going to work. That job came to an end… he had nothing. So, I had to find him tins with ringpulls, because he had no cutlery. He had nowhere to cook, so he was going to be eating out of a tin until he could find somewhere to live.”

There is a full transcript of the interview with Russell here.

While I’m at the foodbank, a housing officer arrives. She’s stopped at the foodbank to collect a parcel for a tenant who can’t make the trip himself.

She says that benefit cuts – “cuts in housing benefit…cuts in ESA – have already had “a big dominoes effect… Demand [for housing association accommodation] is going up massively. Even in the last year, we’ve had a significant change from people with just general housing problems to the majority of people [needing help] because of the reduction in benefits.”

According to Shelter datasets, the number of Poole households in temporary accommodation was 95 in the first quarter this year – up from 72 in the first quarter last year. The number of households on council waiting lists grew from 3908 in 2010 to 4103 in 2011.

The housing officer says that her job was once about fixing problems and finding people appropriate housing. Now it’s about shoving people into gaps. She doesn’t imagine that will end well.

“The people who were already struggling who are now getting to the end of their tether…. Then, you’ve also got people with mental health issues who can’t go into shared accommodation, but unless they’re on mid-rate DLA, or they’ve been in supported accommodation in the past, that’s all that they’re being offered. In their circumstances, it’s wrong.”

Fighting off people’s creditors is another challenge.

“Creditors are being more and more harsh with what they’ll accept as payments for debts. Before, you used to be able to liaise with[creditors] and come to some agreement. Now, the agreements are on their terms… There are people who can’t pay… they had an agreement with that creditor to pay off that debt at that amount, but now they can’t afford it, because he’s lost his job, or she’s lost her job. You go back to the creditors and they say – “Nope, that’s what the agreement was. They have to find the money from somewhere.”

There is a full transcript of the interview with this housing officer here.

———————

Weymouth

Image (by Deptfordvisions): Weymouth memorial to three fishermen drowned off Portland Bill, May 2012.

When the sun is out, Weymouth is a very pretty place: curved waterfront, miles of sanitary (dogs aren’t allowed on it) yellow sand, cafes, bars, beach trampolines, deckchairs, fettered donkeys and an inviting, deceptively shallow sea.

I fluff away a lot of time trying to decide whether or not to mention this prettiness. I think of this particularly when I talk to Dave Mitchen* and Rob Davies* at the picnic tables outside the Pavilion. Mitchen and Davies are both long-term unemployed and both on benefits. There is, as I’ve observed, little sympathy for people in either of those categories. It occurs to all three of us that somebody somewhere will feel moved to observe that people on benefits should be rotting somewhere a little less scenic.

“They have criminalised us to the public” Mitchen tells me as we mope about this. “They done it on purpose.” It is a pity, he says, that the same negative attention isn’t focused on everybody who gets money from the state. “They [members of the government] still get their £300 a day for attending the House of Commons. Yeah – tax free and subsidised bars and restaurants.”

“It’s like that Tory woman said.” Davies observes. “Two rich boys, posh boys – yes.”

“They’re doing too much too fast,” Mitchen says.

“They’re doing too much full stop,” Davies says. “Never mind the speed of it. They just shouldn’t be doing it. They are hitting the poorest people.” He spots a large pile of partly-dried birdpoo on the picnic table. “Hey,” he says. “Aren’t we lucky. Have you got a tissue, Dave?”

Mitchen is seated in a motorised wheelchair. He had polio as a child and then a stroke. He also has spinal problems. He gets housing benefit, council tax benefit and income support. He’s also on disability living allowance. The possibility that he may lose that is causing him concern. The government plans to begin to cut the DLA budget by 20% as it phases DLA out and brings in a new personal independent payment. Mitchen will be reassessed – even though he was given a lifetime DLA award in 1986, because his disability is severe and not likely to improve. He used his DLA to pay for an adapted car. “If they’re going to say – okay, you’re not going to get it…that’s your independence [gone]. They don’t realise the effect that’s going to have.”

“I think they do now and they don’t care,” Davies says morosely. “They want to put me into poverty.” He says that he’s well on his way there. A couple of weeks ago, he failed his ESA work capability assessment. He is now expected to find work. He was a bricklayer for years, but developed chronic fatigue syndrome. “I worked ever so hard and all my holidays – I would go backpacking for weeks on end, to Cornwall Wales, walking all the way. That was nearly all my holidays like that…”

He says that he found his Atos assessment humiliating. “She felt my muscle tone in my legs and my arms and asked me to raise my left leg and right leg.”

It hardly matters what she found there, Mitchen says. Even if there was work around, he thinks it is unlikely that he or Davies would be chosen for it. Both men are in their 50s. “Who is going to employ a disabled person at the age of 58 with only six or seven years work in him?” Mitchen says.

“We need an uprising across the world,” Davies says.

“Yeah,” Mitchen and I say. A friend of theirs, Bob, arrives then. He’s thrilled to pieces. He says that he’s a member of a large choir which will be singing at the Olympics.

“They call him Bob the Confused,” Davies says.

Policy changes affecting, or likely to affect, these people:

– New limits (from 30 April 2012) of eligibility for contributions-based employment and support allowance to a year. Being found fit for work and placed on jobseekers’ allowance.

– Government proposals to cut benefits to people with drug and alcohol problems

– Phasing out of disability living allowance and introduction of the personal independent payment.

——————-

Back down on the Pavilion, a couple of days after the job club disaster, I ask Sean Needham to tell me what the country’s real problems are.

The question makes him angry. He grips the pier railings and his eyes narrow as he looks at me. I decide to look out over the sea.

“There’s too many people here,” he says bitterly. He nearly shouts it. He does shout it, really. He tells me that he lives in a tiny studio flat in a crowded block up the hill a bit. “I’ve been there for years. What do you expect. It’s just people my age. I’m never there during the day, anyway. I’m always out…[It’s all right here] in the summer, but the winter is a bit bleak.”

I’ve read part one of this report as well, and I identify totally with the people interviewed.

Last year I was told that I would have to pay nearly £3000 (I thought it was £2700, but I forgot that it’s paid four weekly) out of my benefits back to the local authority for my care. I used to receive the care free until I was forced to give up my professional work just over 2 years ago, but now I have less income, I have to pay this amount; that doesn’t seem fair.

I might have been just OK, but I have debts that I’m trying to pay off in case I lose my PIP and ESA next year. I was already worried sick because I will have to pay around a £100 every four weeks from next April for the bedroom tax, and no one knows yet what the Universal Credit rates will be.

I had to seek anxiety therapy due to all of the uncertainty. I had recently started to feel a little more positive, and then last week the bombshell hit. I had a care reassessment, and I was told that the majority of the things that carers were doing for me, like laundry, stacking/emptying the dishwasher, shopping/running errands, accompanying me out pushing my wheelchair, emptying and lighting my 2 multi fuel burners (my only source of heating and hot water) and carrying in coal, and so on, in fact all of the things that a healthy person would need to attend to inside and outside the home, is no longer funded. Overall, the local authority are reducing my care package by over 75%; it is going down from 4 hours a day to 1, and the extra 4 hours I was granted to help me get out, and to fund hobbies is being scrapped completely.

The government speak about ‘choice’ and ‘personalisation’, but my local authority now dictate exactly what you can do with your assigned hours. Only a half hour visit in the morning to make sure that I’m OK in and out of the shower, and a half hour in the evening to cook a meal as, among other things, I can’t eat highly processed food due to IBS. I’m not allowed to use this hour a day for any other activity.

I have substantial but not critical needs. I can’t walk very far without a wheelchair, which I cannot self propel, I have extreme muscle weakness, pain in all muscles, and overwhelming fatigue, deteriorating painful and cracking joints all over my body due to muscle weakness, and I’m not able to lift anything even slightly heavy without badly hurting myself. The last time I tried to carry a coal bucket, I pulled all of the muscles in my neck, arm, and shoulder blade and trapped a nerve below my shoulder blade; it took months for me to recover. If I have a spasm I can’t move, so I could be put in a position of waiting all day for a drink and food until a carer came, and possibly soiling myself as well. Any slight activity brings on excruciating neuropathic pain, which can take weeks to subside, so there is no way that I could sustain any activity for long. I’ll be the ridiculous position of being washed in the shower, but putting dirty cloths back on.

The assessor told me to use my DLA to buy in extra care, but I told her that I pay a big chunk, over half of that back to the local authority, and they won’t reduce my charge even though my care package is being slashed. I worked out, that after paying for regular deliveries of food (since no shopping is allowed), paid my extra heating costs and the other jobs I pay out for apart from my care needs, it will leave me with £10 per week to fund the extra care and my transport needs. It’s a joke.

I now have to sack my main carer, and cut the hours of the 2 remaining ones. To top it all, the assessor said she would call me last Thursday to confirm my care plan hours; she said that my circumstances were not clear cut, so she would try to appeal to her managers, but nearly a week later I’ve head nothing.

So I feel like my life is in the balance. I am physically and mentally sick over it. I can’t sleep and I don’t want to eat. Prior to receiving the care I was in a desperate situation, living in a smelly dirty home, with no clean clothes or bedding, and no fires lit, living on sandwiches. My illness has deteriorated further since then, so it looks like come this winter and especially winter 2013, I’ll be back in the same situation. I don’t have critical needs so I can’t go in a home; like most, I don’t want to.

I’ll repeat what I have written at the end of a comment about the care issue in the Guardian today:

‘Personalisation? Trouble is local authorities seem to have forgotten there’s a ‘person’ contained in that word: social workers singing as they knock on your door; humming along as they type into their laptops; smiling from ear to ear; telling you as they walk out ‘it’s a good job you have that laptop’ (though I’m sure she’s a good person, her general happiness was somewhat distasteful), whilst simultaneously destroying peoples’ lives (my main carer has lost her job as well, and it’s one of the worst places in the UK to find work).

No, rather, local authority policy in this case just got very ‘impersonal’ indeed.

Pingback: Greece, cuts, cruelty and why I voted for the Golden Dawn – interview 1 – Kate Belgrave

Pingback: These people are not shirkers | Kate Belgrave

Pingback: These people are not shirkers (cross/re-post) « Launchpad: By and for mental health service users

Pingback: Mental health, Falkirk and the diversions of the political class | Kate Belgrave

Pingback: Expendable people – a list | Kate Belgrave

Pingback: Chris Huhne, rehabilitated. Too bad for everyone else. | Kate Belgrave

Pingback: Social security and voting Tory | Kate Belgrave

Pingback: Social security and voting Tory - News4Security

Pingback: Telling addicts to get sober or get out doesn’t work. I tried that for years myself. | Kate Belgrave